“Informed teens are much more likely to wait for first intercourse, use condoms and other barrier and birth control methods at first intercourse, and are more likely to take responsibility regarding their own sexual health.” Emily E. Prior

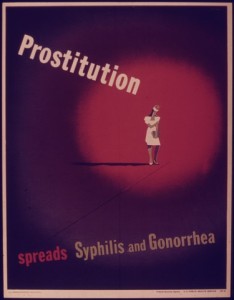

But not just any information given to teens will produce such a result. For decades, sex education programming in schools across America have used an agenda of fear tactics to teach teens that sex is bad, sexual pleasure is sin, and homosexuality is a mental illness. It’s time that Americans realize this approach of scaring teens from having sex doesn’t work: 46.8% of high school students report having engaged in sexual intercourse, with the rate increasing to 63.1% for high school seniors.

Using fear tactics in sex education is like hanging on the edge of a cliff: a person doesn’t have to be forced on to the edge to experience fear to know how dangerous it is. Similarly, if teachers taught comprehensive sex education using open, honest communication, then students will stay away from the cliff’s edge and practice safe sex.

So if you can’t scare teens from having sex, what else can we do?

The exact opposite of what doesn’t work: educate teens using sex-positive approaches. Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) created the concept of sex-positive and sex-negative when he hypothesized that some societies view sexual expression as essentially good and healthy, while other societies take an overall negative view of sexuality and seek to repress and control the sex drive. Does the later ring a bell?

Emily E. Prior, the Director of the Center for Positive Sexuality, describes being sex-positive as “not limiting sexual scripts to reproduction and procreative-only sex, but also the pleasurable, rewarding, and nonprocreative aspects of sexuality.” However, Prior warns that this does not mean educators should start “promoting” sex, but rather, “recognizing sexuality as a normal, healthy part of being a person and that everyone is a sexual being.” But this is not a new concept: just check out the Dutch.

So how can educators utilize sex-positivity in the classroom? Prior has a tip.

First, educators can create a sex-positive classroom space: “A sex-positive space,” Prior begins, “is an open and accepting space where [students] can feel comfortable to be themselves, communicate with one another, and be accepting, not just tolerant, of others’ differences related to sexuality and sexual behavior.” This means that students who identify with the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and questioning (LGBTQ) community will not be excluded or stigmatized, which typically happens in a sex-negative space. Also, as Prior eloquently puts it, a sex-positive approach “allows teens to recognize their personal and sexual development as an ongoing, lifelong, and healthy process. By allowing for communication and individual expression, teens are much more likely to make healthy choices that work for their bodies.”

The differences between a sex-positive approach to sex and the sex-negative approach to sex, with the former reflected in comprehensive sex education and the later used in abstinence-only education.

Sounds great to me! And it should sound great to everyone who wants to help teens become sexually responsible and reduce America’s high rates of unintended teen pregnancies and transmission of STIs and HIV–and who doesn’t? Let’s face it: teens are going to have sex no matter if we try to scare them or not, so we might as well suck it up and give them the information and tools they need to be safe once they decide to have sex, be it during high school or after marriage.

Creative Commons Image by: epSos.de

Creative Commons Original Image by: bluekdesign

Imaged Edited by: Alifa Watkins